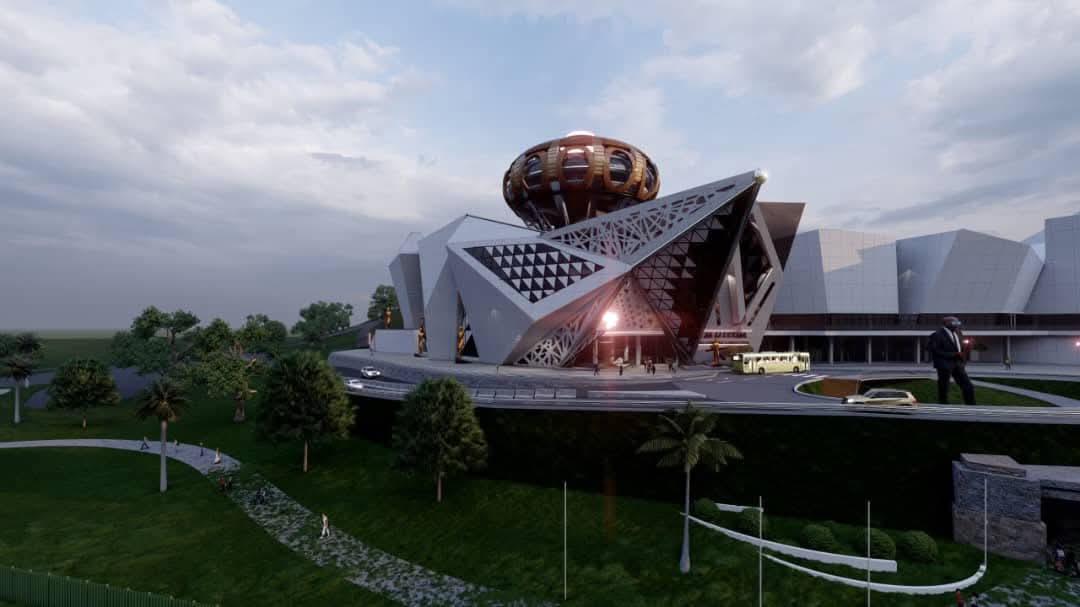

BRAND NEW cities that are privately funded by foreign companies and have little reliance on government infrastructure are going up in Kenya, Nigeria, the DRC, Ghana and Zambia. Something to look forward to: A glimpse of a city of the future While the link roads are being built for SA’s new Chinese-funded US$6.2bn city east of Jo’burg, a rash of brand spanking new cities are changing skylines across Africa. And most of them are private ventures, offering tens of thousands of urban Africans the opportunity to live in comfort “off the grid”, insulated from the chaos that characterises so many of the continent’s cities. By far the most ambitious project — and the largest real estate development on the continent, according to Deloitte — is Centenary City, an $18.6bn smart eco-city for 137,000 residents and 500,000 daily commuters that is being built from scratch outside the Nigerian capital Abuja, a few minutes’ drive from the Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport.

Developed by Abu Dhabi-based Eagle Hills in a public-private partnership with the Federal Capital Territory, Centenary City will form a free-trade zone and have its own liberal banking and tax regulations. Construction has begun on the first phase, 25ha of bespoke hotel and residential space. The entire city is designed to include efficient transportation, biomimetic water and waste management, and finance, commerce, science, sports, medical and cultural facilities. It will be independent of Abuja, thanks to its own 500MW gas-fired power station.

It is scheduled to be operational and occupied by 2024. However, the city’s construction has been dogged by controversy. A public hearing by a committee of the Nigerian House of Representatives is under way into allegations that Centenary City Company Plc., owned by corporate lawyers Paul Oki and Boma Ozobia, had varied from, and had been given special waivers of, federal regulations, while a land claim by indigenous Izzi evicted by the development is before the courts. There are three types of new cities in Africa, all characterised by being greenfields developments only slightly reliant on existing infrastructure.

First are the self-sufficient satellite cities on the outskirts of major urban areas, such as Centenary City. Second are the tech hubs, like the $14.5bn Konza Technology City for 200,000 residents in Kenya, 64km south of Nairobi. It is intended to become the core of the continent’s “Silicon Savannah”. Third are dormitory cities for ports and free-trade zones, for example the 78,000-resident King City, designed to serve the Ghanaian port of Takoradi, which is rapidly expanding thanks to offshore oil wells. A few, like Luanda’s $5.5bn ring of five new Chinesebuilt cities, are state funded, erected within months and occupied mostly on a rent-to-buy basis. But the majority are private ventures such as Jo’burg’s Modderfontein New City, intended to be built in phases over a decade or two and aimed at attracting a mixture of buyers and tenants.

The mushrooming of these “insta-cities” was the focus of a lengthy Christian Science Monitor feature in 2015. It criticised the class exclusivity of the $6bn Eko Atlantic city for 250,000 wealthy residents and an additional 150,000 commuters that is going up on the reclaimed foreshore of Victoria Island in Lagos. Prof Vanessa Watson of the University of Cape Town’s African Centre for Cities has warned that though rapid growth in Africa has excited property developers, a likely result of “these fantasy plans” is a “steady worsening of the marginalisation and inequalities that already beset these cities”.

Some plans, such as those announced in 2013 for a $10bn Hope City tech hub that was supposed to spearhead an ICT revolution in Ghana, have remained stillborn, while others, like one-time ghost city Kilamba in Angola, experienced birth pangs because of the absence of proper transport integration, billionaire investment banker Stephen Jennings. Rendeavour is responsible for Ghana’s King City and the new 90,000-resident Appolonia City of Light outside of Accra — with a combined price tag of $1bn. Rendeavour is also developing Kenya’s $2.6bn Tatu City for 70,000 residents and 30,000 day visitors outside Nairobi, the $758m Kiswishi City outside Lubumbashi, DRC, and other developments in Nigeria and Zambia.

All these were initially funded by Jennings’s Moscow-based investment bank Renaissance Capital, but in 2013 Jennings divested from Russia, retaining only the African cities projects under Rendeavour. Rendeavour spokesman Tim Beighton tells the Financial Mail from Lagos that the company’s developments deliberately included affordable and low-income housing “so that those who provide the services are also able to live there”.

Beighton sees mixed-income housing as vital to ensure the socioeconomic viability and vitality of the new cities, which were all integrated into national developmental plans and local municipal administrations. He says housing finance differs across the five countries. There is a mature and fairly strong mortgage market in Kenya but “a cash-and-carry economy” in Nigeria that has made accessing finance difficult, though Beighton says government is looking at creating a mortgage market. In this way, new private cities are driving the development of new financial instruments and an improvement of state service infrastructure.

They also attract further investment. Tatu City is Rendeavour’s flagship, and sod was broken there in 2011 — but development was delayed for two years by a court case in which Tatu City’s minority shareholders unsuccessfully sued the company to either have it wound up or let its shares be bought out by the majority. By July 2015, the developers said construction had begun on the city’s residential suburbs, where 150 plots had been sold and 13 firms, including Unilever, the Bidco Oil Refinery and Dormans Coffee, had signed deals for sites. Dormans’ 4ha plant, now under construction, is designed to process, package and ship more than 15,000t of coffee a year.

In January, SA-based Nova Academies’ secondary school for girls opened in Tatu, a sign that the new city’s future generation has finally arrived.no mortgage market and no rent-collection system, though it is now occupied. The largest developer of new cities across Africa is Rendeavour, which was founded in 1995 by Kiwi.