An example of a biophilic city is Singapore. Singapore wanted to become “A City in a Garden.” To accomplish this goal, parks and green areas were built all around and tied together by 200 kilometers of Park Connectors, elevated walkways and canopy walks.

Biophilia is our innate human desire to connect with the living world. Popularized by the Harvard biologist and entomologist, E. O. Wilson, he said biophilia is “the innately emotional affiliation of human beings to other living organisms.” Urban Biophilia stands as a model to meet this human need through the lens of Landscape.

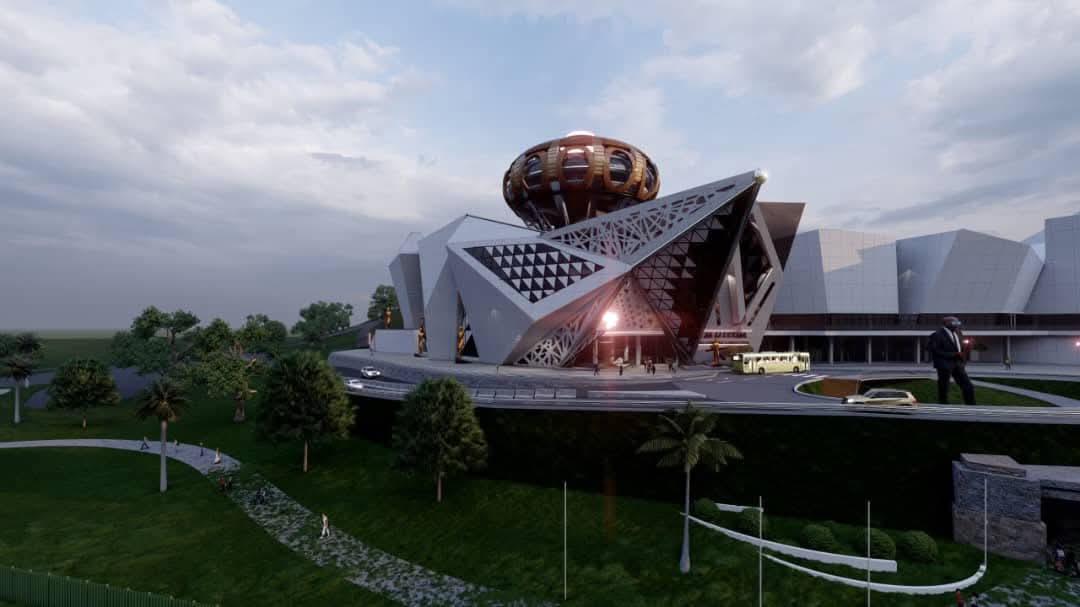

By taking a psychological perspective on the effect the natural environment has on people, landscape has been moulded and manipulated in search of what really is an environment that can restore the negative syndromes that city life presents to its people. Biophilic Design is an innovative way of designing the places where we live, work, and learn. We need nature in a deep and fundamental fashion, but we have often designed our cities and suburbs in ways that both degrade the environment and alienate us from nature.

The recent trend in green architecture has decreased the environmental impact of the built environment, but it has accomplished little in the way of reconnecting us to the natural world, the missing piece in the puzzle of sustainable development. The purpose of biophilic design is to incorporate nature into the built environment. It improves air quality and food security, making it very sustainable. Views to nature can shorten hospital stays and increase employee productivity. It can also increase property value.

Biophilic Design in the Workplace. As work psychologists we have an enduring interest in both the individual and environmental factors that influence business outcomes. In particular, the interaction between an individual and their work environment can be a crucial determinant of both an employee’s success and happiness in his or her role. The concept of biophilia highlights an innate connection between humans and nature, which more recently has been recognised as a key consideration when designing and developing workspaces.

The idea of incorporating nature into the built environment through biophilic design is less often seen as a luxury in the modern workplace, but rather as a sound economic investment into employees’ health, well-being and performance. Source – Human Spaces report. What makes work feel good? For modern organisations and their people, it’s about much more than the end goal of productivity and profit. How we gain meaning, a sense of well-being and of purpose in the workplace is just as vital, not only to feel good but to perform effectively too.

Increasingly, employers and employees themselves are engaging in this debate about a more comprehensive view of work and the role it plays in our lives, as are governments and societies with the growth of projects measuring national well-being across the world. A connection with the natural world is a big part of that discussion however we frame it – escaping the concrete jungle, achieving a better level of balance or simply being in a space that is enjoyable.

The increasing academic and organisational interest in biophilia and biophilic design is driven by the positive outcomes that it can help create for individuals and businesses. It begins with identifying that here is a major movement of populations globally into urban areas – we are as disconnected from nature as we have ever been. Oppotunities therefore exist within this realisation, falling squarely in Biophilic Design.

A background to biophilia The ‘Biophilia Hypothesis’ suggests that there is an instinctive bond between human beings and other living systems. It literally means a love of nature, and suggests an ingrained affinity between humans and the natural world. Therefore, biophilic design is a response to this human need and works to re-establish this contact with nature in the built environment. Ultimately, biophilic design is the theory, science and practice of bringing buildings to life and aims to continue the individual’s connection with nature in the environments that we live and work in every day. In today’s contemporary built environment, people are increasingly isolated from the beneficial experience of natural systems and processes.

Yet it is often natural settings that people find particularly appealing and aesthetically pleasing. So by mimicking these natural environments within the workplace, we can create workspaces that are imbued with positive emotional experiences. It is often the case that we don’t take enough time to immerse ourselves in nature, or appreciate the living systems that exist everywhere around us, making it vital for us to incorporate nature into our day-to-day environments. Existing research into the impact of biophilia in the workplace demonstrates tangible benefits for individuals and their organisations.

Contact with nature and design elements which mimic natural materials have been shown to positively impact health, job performance and concentration, and to reduce anxiety and stress. In turn, there are proven links between work environments exhibiting biophilic design and lower staff turnover and sickness absence rates. Although these benefits have all been comprehensively proven in isolated studies, there are few if any cross[1]country studies that examine the preferences of individual employees in terms of biophilic design and the impact of meeting those preferences.

Biophilic design brings offices to life, and goes far beyond the practical benefits of a single plant recycling air behind the reception desk of a high-rise building. Much research into biophilia supports the positive impact that this nature contact can have. Studies have shown the diversity of that impact includes increasing a customer’s willingness to spend more in a retail environment, increasing academic performance amongst school children and even reducing anxiety and stress before medical procedures. In the workplace we are concerned with biophilic design in relation to employee outcomes, specifically in the areas of well-being, productivity and creativity.

Findings show that natural elements in the workplace are determinants of these three aspects. The research has shown that overall, those with natural elements present in their workspace report higher levels of creativity, motivation and well-being. The findings can be integrated to provide practical insights into modern workspace design, for example internal green space and natural light are positively linked to greater productivity and those with live plants in the office reported higher levels of well-being than those without.

For example, in patient waiting rooms with murals depicting natural scenes such as mountains, sunset, grassy areas and stone paths patients felt significantly calmer and less tense than those sat in a waiting room with plain white walls9. In the work environment our research presents similar findings, showing that the use of mute colours (brown and grey specifically) were associated with greater reported levels of stress. In contrast, employees in offices with bright accent colours (red, yellow, purple, orange, green and blue) reported lower levels of stress.

Ultimately it is important for organisations to recognise the particular colours that have the best impact in terms of employee well-being and consider how these colours can reflect the natural elements that inspire us. “…the enjoyment of scenery employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it, tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus, through the influence of the mind over the body, gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system. ” Frederick Law Olmsted, 1865 16 structure & design Biophilia may also help explain why some urban parks and buildings are preferred over others.

For decades, research scientists and design practitioners have been working to define aspects of nature that most impact our satisfaction with the built environment. But how do we move from research to application in a manner that effectively enhances health and well-being. Over 500 publications on biophilic responses have been mined to uncover patterns useful to designers of the built environment like interior designers, architects, landscape architects, urban designers, planners and also health professionals, employers and developers, as well as anyone wanting to better understand the patterns of biophilia.

These 14 patterns have a wide range of applications for both interior and exterior environments, and are meant to be flexible and adaptive, allowing for project[1]appropriate implementation.

14 Patterns of Biophilic Design

- Visual Connection with Nature

- Non-Visual Connection with Nature

- Non-Rhythmic Sensory Stimuli

- Thermal & Airflow Variability

- Presence of Water

- Dynamic & Diffuse Light

- Connection with Natural Systems

- Biomorphic Forms & Patterns

- Material Connection with Nature

- Complexity & Order

- Prospect

- Refuge

- Mystery

- Risk/Peril

Nature in the Space Nature in the

Space addresses the direct, physical and ephemeral presence of nature in a space or place. This includes plant life, water and animals, as well as breezes, sounds, scents and other natural elements. Common examples include potted plants, flowerbeds, bird feeders, butterfly gardens, water features, fountains, aquariums, courtyard gardens and green walls or vegetated roofs.

The strongest Nature in the Space experiences are achieved through the creation of meaningful, direct connections with these natural elements, particularly through diversity, movement and multi[1]sensory interactions. Nature in the Space encompasses seven biophilic design patterns:

- Visual Connection with Nature. A view to elements of nature, living systems and natural processes.

- Non-Visual Connection with Nature. Auditory, haptic, olfactory, or gustatory stimuli that engender a deliberate and positive reference to nature, living systems or natural processes.

- Non-Rhythmic Sensory Stimuli. Stochastic and ephemeral connections with nature that may be analyzed statistically but may not be predicted precisely.

- Thermal & Airflow Variability. Subtle changes in air temperature, relative humidity, airflow across the skin, and surface temperatures that mimic natural environment

- Presence of Water. A condition that enhances the experience of a place through seeing, hearing or touching water.

- Dynamic & Diffuse Light. Leverages varying intensities of light and shadow that change over time to create conditions that occur in nature.

- Connection with Natural Systems. Awareness of natural processes, especially seasonal and temporal changes characteristic of a healthy ecosystem.

Natural Analogues Natural

Analogues addresses organic, non-living and indirect evocations of nature. Objects, materials, colors, shapes, sequences and patterns found in nature, manifest as artwork, ornamentation, furniture, decor, and textiles in the built environment.

Mimicry of shells and leaves, furniture with organic shapes, and natural materials that have been processed or extensively altered (e.g., wood planks, granite tabletops), each provide an indirect connection with nature: while they are real, they are only analogous of the items in their ‘natural’ state.

The strongest Natural Analogue experiences are achieved by providing information richness in an organized and sometimes evolving manner.

Natural Analogues encompasses three patterns of biophilic design:

- Biomorphic Forms & Patterns. Symbolic references to contoured, patterned, textured or numerical arrangements that persist in nature.

- Material Connection with Nature. Materials and elements from nature that, through minimal processing, reflect the local ecology or geology and create a distinct sense of place.

- Complexity & Order. Rich sensory information that adheres to a spatial hierarchy similar to those encountered in nature. Nature of the Space Nature of the Space addresses spatial configurations in nature. This includes our innate and learned desire to be able to see beyond our immediate surroundings, our fascination with the slightly dangerous or unknown; obscured views and revelatory moments; and sometimes even phobia inducing properties when they include a trusted element of safety. The strongest Nature of the Space experiences are achieved through the creation of deliberate and engaging spatial configurations commingled with patterns of Nature in the Space and Natural Analogues.

Nature of the Space encompasses four biophilic design patterns:

- Prospect. An unimpeded view over a distance, for surveillance and planning.

- Refuge. A place for withdrawal from environmental conditions or the main flow of activity, in which the individual is protected from behind and overhead.

- Mystery. The promise of more information, achieved through partially obscured views or other sensory devices that entice the individual to travel deeper into the environment.

- Risk/Peril. An identifiable threat coupled with a reliable safeguard.

Source: 2014, 14 Patterns of Biophilic